Arxius de Miscel·lània Zoològica. Volum 20 (2022) Pàgines: 53-58

Notable sighting record of the Himalayan vulture Gyps himalayensis (Hume, 1869) in the outer western Himalayas, Uttarakhand, India

Kukreti, M., Nautiyal, A. R. G.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.32800/amz.2022.20.0053Descarregar

PDFCita

Kukreti, M., Nautiyal, A. R. G., 2022. Notable sighting record of the Himalayan vulture Gyps himalayensis (Hume, 1869) in the outer western Himalayas, Uttarakhand, India. Arxius de Miscel·lània Zoològica, 20: 53-58, DOI: https://doi.org/10.32800/amz.2022.20.0053-

Data de recepció:

- 05/07/2022

-

Data d'acceptació:

- 10/10/2022

-

Data de publicació:

- 26/10/2022

-

Compartir

-

-

Visites

- 2939

-

Descàrregues

- 1168

Abstract

Notable sighting record of the Himalayan vulture Gyps himalayensis (Hume, 1869) in the outer western Himalayas, Uttarakhand, India

We report the sighting of a large flock of immature Gyps himalayensis (Hume, 1869) in the Garhwal Himalayas area of the outer Himalayan range. This avian species is classified as near–threatened according to the IUCN Red List. We recommend future surveys and documentation of breeding and juvenile vagrant sites in this area in order to determine population numbers, moult and breeding schedules, and population trends in the area.

Key words: Gyps himalayensis, Garhwal Himalayas, Threatened birds, Avian biodiversity

Resumen

Registro de una destacada observación de buitre del Himalaya Gyps himalayensis (Hume, 1869) en el Himalaya Occidental Exterior, Uttarakhand, India

Presentamos una observación de notable interés de una gran bandada de Gyps himalayensis inmaduros (Hume, 1869), una especie de ave casi amenazada según la Lista Roja de la UICN, en el macizo de Garhwal de la cordillera exterior del Himalaya. Recomendamos estudiar y documentar las zonas de cría y de vagabundeo juvenil para establecer el número, muda y biología de cría del buitre del Himalaya a fin de determinar las tendencias de la población en el área de estudio.

Palabras clave: Gyps himalayensis, Macizo de Garhwal, Aves amenazadas, Biodiversidad aviar

Resum

Registre d'una destacada observació de voltor de l'Himàlaia Gyps himalayensis (Hume, 1869) a l'imàlia Occidental Exterior, Uttarakhand, Índia

Presentem una observació de notable interès d’una gran bandada de Gyps himalayensis immadurs (Hume, 1869), una espècie d'ocell gairebé amenaçat segons la Llista Vermella de la UICN, al massís de Garhwal de la serralada exterior de l'Himàlaia. Recomanem estudiar i documentar les zones de cria i vagabunderia juvenil per establir–ne el nombre, la muda i la biologia de cria a fi de determinar les tendències de la població a l'àrea d'estudi.

Paraules clau: Gyps himalayensis, Massís de Garhwal, Ocells amenaçats, Biodiversitat aviària

The Himalayan vulture is found up to an elevation of 5,500 m throughout central Asia, in western and central China, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and the eastern Himalayas range of India, Nepal, Bhutan, and Mongolia (BirdLife International, 2022). On the Indian subcontinent, this species is resident in the high mountains of the Himalayas and it winters in the southern to northern Indian plains (Alström, 1997; Praveen et al., 2014; Grimmett et al., 2016). Here we report the first sighting of G. himalayensis in Kholachauri village in the Pauri Garhwal district, in the outer western Himalayas. To date there has been no authenticated published research regarding its abundance and seasonality in this area or adjoining areas of the Garhwal Himalayas other than the odd sighting such as those of Atkore and Dasgupta (2006) near the town of Devprayag and Chowfin and Leslie (2021) from the Gadoli and Manda Khal village areas close to Pauri town in the Pauri Garhwal district.

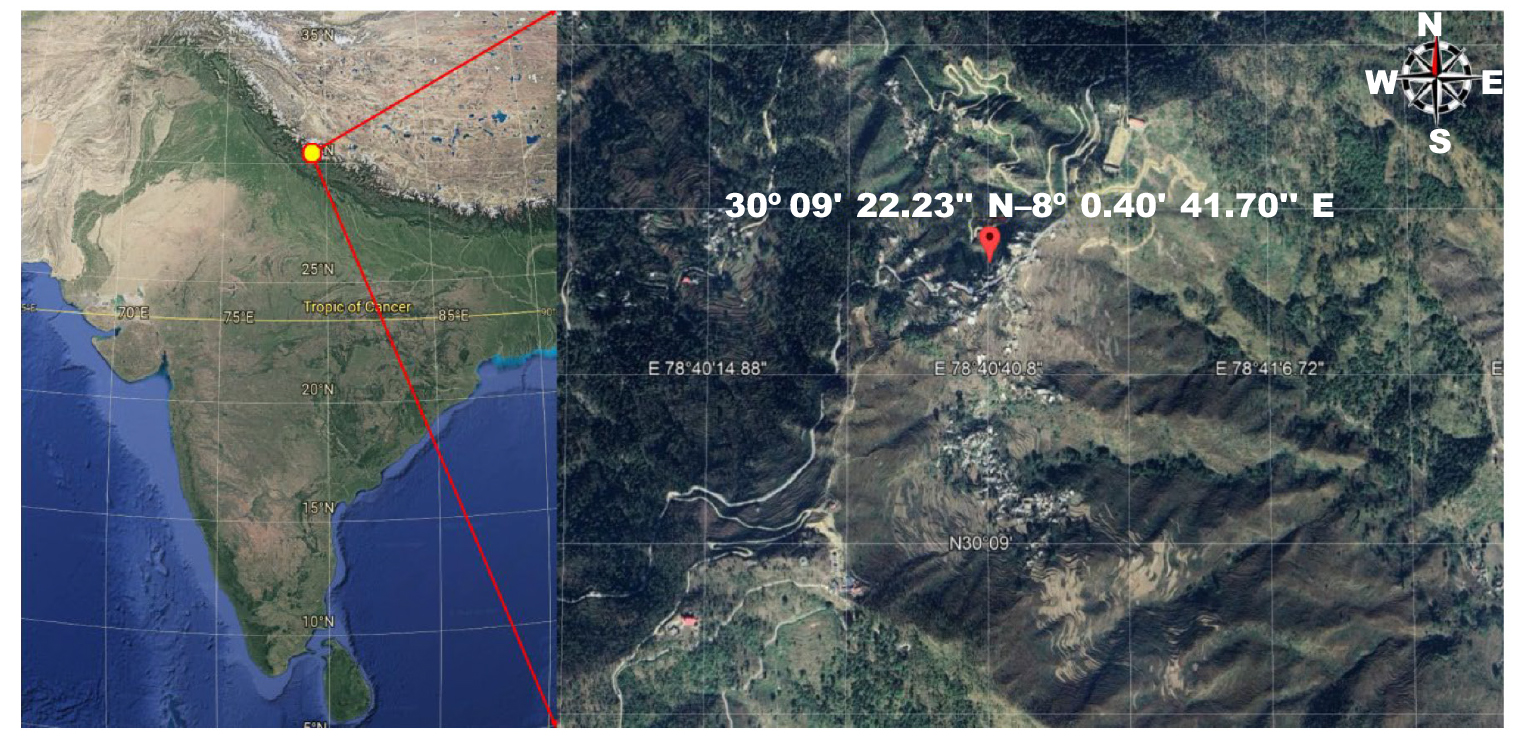

Kholachauri, where the current observation was reported, is a small village located 13 km west of the Pauri district headquarters (fig. 1). This rural area has a large number of modern concrete houses on the Pauri–Devprayag state highway and adjacent traditional houses with nearby agricultural land sharing its boundary with civil and reserved forest areas with dominant tree species of Pinus roxburghii (Sarg.).

Fig. 1. Imágenes de satélite de la zona de estudio (fuente: Google Earth Pro).

On March 8th 2021, while driving from Pauri town to Kholachauri via the Pauri–Devparyag motor road, we observed a large flock of G. himalayensis (fig. 2) in the centre of Kholachauri village, a part of Pauri forest range of Garhwal forest division (30º 09' 22.23'' N–78º 0.40' 41.70'' E; 1,589 m a.s.l.). We observed some 63 individuals on the ground and about nine individuals soaring in the sky. Most were immature (we could not ascertain the calendar year of age) and within a distance of 20 meters to the right of the road, at around 8 a.m. The birds were feeding on a cow carcass, likely dumped by nearby villagers. Some of the birds were very large immature specimens, aggressively feeding and driving off the others. Some juveniles were perching on a chir pine tree (Pinus roxburghii) (fig. 3). The flock remained there until 2.40 p.m. when they took flight and soared towards the higher hills to the north.

Fig. 2. Un numeroso grupo de G. himalayensis juveniles en Kholachauri, un pueblo de Pauri Garhwal, en el oeste de la cordillera exterior del Himalaya (fotografía de Aishwarya Raj Gaurav Nautiyal).

Fig. 3. Un juvenil de G. himalayensis posado en un pino P. roxburghii (fotografía de Mohan Kukreti).

This large gathering of G. himalayensis immatures makes the area a potential conservation site in India for this vulture whose numbers are declining in its native habitats. From the lower Garhwal Himalayas a large flock of 39 individuals was recorded from the Mundal forest range (in the Pauri Garhwal district) of Rajaji National Park (Das et al., 2011), and 120 individuals were identified in the Dehradun district at Jhajra carcass dumping site (Balodi et al., 2018), but for the Pauri district we believe our observation is probably the first record of a large flock (with more than 60 individuals) in the high elevational site of the Garhwal Himalayas. The adults of this species are mainly found in their breeding ground, while immature specimens are found as vagrants (Naoroji, 2006; Rasmussen and Anderton, 2012). In the context of the Indian subcontinent, immatures have been found migrating to the lowlands of India, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Pakistan (Das et al., 2011; Botha et al., 2017). This species was found to be an altitudinal migrant in Nepal (Virani et al., 2008), part of the Indian subcontinent, and shares its territorial boundary with the state of Uttarakhand, where this site is located. This altitudinal migration may be one of the reasons for the large gathering at this site. Another possible reason is that this species is exclusively a carrion feeder (del Hoyo et al., 1994), and the significant reduction of wild carrion in the upland range of this species (Li and Kasorndorkbua, 2008) may be responsible for the wandering population. The present observation site is located between a civil forest and the reserve forest area of Garhwal forest division (a protected area under state law), and there is a continuous movement of local villagers for wood and fodder for livestock in this protected area. The laws for the protection of forests and wildlife (Indian Forest Act, 1927 and Wildlife Protection Act, 1972) should be strictly enforced to save this globally threatened species and site from anthropogenic activities.

The Himalayan vulture species is in the near–threatened category (IUCN, 2022). In India, it is a species of moderate status as long–term analysis are lacking. It qualifies as a species of high concern (SoIB, 2020). Besides the anthropogenic activities, the major threat to this species is the use of the non–steroidal anti–inflammatory drug diclofenac in the breeding range. This drug has been found toxic to this and other Gyps species (Das et al., 2011), particularly exposing immatures –inexperienced foragers– to a high risk, especially when separated from a base population in their wandering grounds (Praveen et al., 2014). A study of the breeding population study in a neighboring country, Nepal (Bhusal et al., 2021), suggests that the absence of nest sites, electrocution, forest fires, and carcass poisoning are the limiting factors for negative growth rates of this species. In view of the conservation perspective, we recommend a special task force should be established to conduct long–term population monitoring studies in the areas where they have been sighted and at breeding sites within the country and adjacent countries, with rescue and rehabilitation centers being set up for immature populations, especially close to migratory and carcass dumping areas. Further interventions should include an awareness program for conservation and alternatives to diclofenac, such as meloxicam and other safer agents, should be encouraged (Birdlife International, 2022). Future work should focus on telemetry studies of this species, monitoring transboundary movement and tracking immatures in their foraging grounds.